|

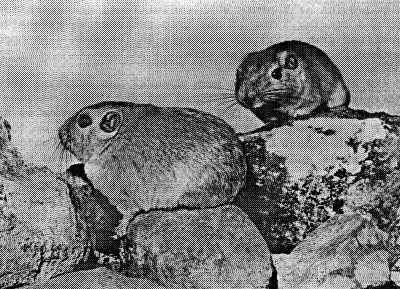

These are stories about two out

of five species of gundi, the desert gundi Ctenodactylus

vali and the Mzab gundi, Massoutiera mzabi. Another

two inhabit the 153 area: Ctenodactylus gundi the North

African gundi—the 'gundi-mouse' which was given to a Swede

in 1774—and the Felou gundi Felovia vae which was

first discovered in its only known colony about a hundred years

go. The fifth lives far off the 153 in the deserts and mountains

of Ethiopia beside the Red Sea.

The Michelin

153 map covers the range of four of five species of the small

furry mammal called Gundi. George and I have been chasing gundis

for the past fifteen years so several 153s have been worn to

tatters. The Map does not have flags on it reading 'Voici, gundis',

so you cannot just set off with it and find a gundi. Our first

expedition to the Algerian Sahara was a flop. We did not know

what we were looking for. We had read about gundis—the comb-toe

rodents or ctenodactylids—but it had not helped. All we knew

was that they lived in rocky areas, were about the size of a

guinea pig and had combs on their toes. Were they to be found

in the sun of a Saharan day or were we destined to be groping

for gundis in the middle of the night? Reports were conflicting.

Did they burrow? Some said yes, some said no. And what did they

do with the combs on their toes? There were plausible stories

of sand being brushed away from burrows and crazy stories of

them combing themselves in the moonlight as they whistled. The

beast became more and more mediaeval, straight out of a bestiary.

There were a few skins and skulls in the Natural History Museum

which gave an idea of size and colour. But colour was not much

help as it turned out because red gundis were invisible against

red sandstone, blond against pale, black against black. And

what of the black gundis? Well, we have not yet seen one.

No

one was able to tell us anything useful about the elusive beast

until we met Bouzidi the Chaamba. And he told us that the way

to find it was to listen or spot its 'crottes'. Gundis drop

their pellets on communal dunghills outside their shelters and

use the same ledge for centuries. So you not only have to find

the droppings and recognise them but you have to know how old

they are. Once a good heap has been identified there is nothing

to do but sit on a rock nearby, unpack the binoculars and wait.

If it's 35°C in the shade there is no point in waiting since

gundis are not mad Englishmen but know the right temperature

for sunbathing. So come back and sit in the cool of the morning

or evening. If the topmost crotte on the heap was moist then

something is sure to happen. When the sun comes up—if it's

not too cold and windy—one two three four out onto a rock

shelf, a family of gundis. First face to the sun, then the sides—and, finally, the rump. We quickly learnt that gundis do not

come out in the moonlight and do not comb their hair like the

Lorelei. They scratch with the combs to avoid damaging the fine

fur with their claws. To scratch a rump with a comb on top of

a rear foot puts a gundi in direct competition with Charlie

Chaplin for funny movements.

The desert gundi of western Algeria is

the smallest of the family: chestnut-coloured with nothing but

some bristles for a tail. It can endure a higher temperature

than its relatives in the 153 area: 41°C for eight hours is

not bad for a small mammal. Normally—outside experiments—it keeps to ambient shade temperatures between 15° and 35°.

After

a quick warm-up, gundis come out foraging: sorties to a favourite

clump of Moricandia or, failing something so delicious,

a nibble at a clump of grass. Grass is a standby. Gundis prefer

leaves or the succulent flowers of the Compositae. None

eats insects and they prefer greens to seeds. In emergency,

they can manage on dry stuff for days but in the long term they

need green stuff to stay alive. They do not need to drink. Even

the babies get little liquid. A female cannot spare much fluid

to make milk so her offspring have to adapt to plants quickly.

Gundis are born—never more than three at a time—fully-furred

and open-eyed with big back feet. After a few hours they are

brought out of the shelter and onto a ledge in the sun but at

the slightest sound or shadow the big back feet bounce them

back under the rock. Now you see me, now you don't. The mother

suckles them a moment but, at the same time, feeds them chewed

leaves from her mouth. When she takes them out she may abandon

them and then forget which rock so she has to home in on their

chirps. And what a chirp they make—like a nestful of birds.

When we trapped a Mzab gundi we baited the trap with her babies

and she was in there like a shot—before we could get to

our hide. Catching the babies had been hilarious. Like the mother,

we homed in on them but they were pressed tight into a crack

and it was impossible to prise them out. Gundis love cracks.

The favourite crack in our house is between a radiator and a

wall and these babies were in just such a place only worse with

prickly rock, not a smooth radiator. So Wilma crouched below

with the chech at the crack while George took a deep deep breath

above and blew them down the chimney. Out came one golden puff

into the chech. Then a great big blow—and several blows later

because the sister had her curved claws well hooked in—down

came the second.

The

tawny Mzab gundi has longer fur than the desert gundi. It has

a short fantail instead of bristles. The Mzab gundi lives round

the central mountains of the Sahara and the desert gundi lives

over towards the western dunes.

North

African gundis are caught in a chech so as not to damage the

fur which is easily stripped off. Remarkable for a rodent, no

gundi bites and they can be transported in a cardboard box.

Once, we brought gundis back to England in a shoe box. We have

wandered across Africa—through steamy jungles and over

snowy mountains—to deliver gundis in a box to a pilot of

some airline. We pack them in wood for posting (nails, screws,

thongs, according to local supply). We add sand and leaves.

We have brought bundles of lucerne in the souks of North Africa

from traders who assumed we had a donkey round the corner and

Wilma has been seen running madly across fields in Spain and

France to get at the lucerne. She hasn't been caught yet. In

153 country, there is always Gloria. A daily dose of tinned

milk let down with water from a small pipette keeps. a travelling

gundi in good shape. More of a problem is keeping warm. Gundis

get miserable when the temperature drops below 15°C. In winter,

they keep warm inside the rock by piling up in a heap. When

the sun shines, they are out on a ledge or sheltered from extreme

heat in a breezy nook. It was not easy to provide such facilities

on long journeys to the sunless north.

There

are many French hoteliers who must have wondered what went into

our room in a huge basket and wondered much more when it whistled.

They would have been astounded if they had seen the bed heaped

with furniture to get the gundis near the light bulb with us

curled up in between the chair legs. And what did they think

of the small black pellets they found on sheets in the morning?

One

year leaving Alger by boat, we had to battle with customs for

possession of our Land Rover. There was nothing wrong with our

papers—they just wanted the Land Rover. The gundi boxes were

snugly wrapped in sleeping bags for the sea-crossing. Finally,

George argued his way through the Algerian web of duplicity

and reached agreement for shipping the Land Rover but the boat

was loaded.' The Land Rover would be shipped after us on a freighter.

(The customs officer showed gold teeth when he smiled). As we

steamed out of the dock we saw the sleeping bags being stolen

on the quayside. Death to the gundis. We spent a miserable night

on board with the Captain radioing back to Alger to insist that

the Land Rover should be put on the next freighter as promised.

Thanks no doubt to the French captain, the Land Rover followed

us on a freighter to Marseilles. But the comedy continued. This

time French customs decided they liked the Land Rover and anyway

it was 'pas normal' for it to sail by itself on a freighter

when it was an 'accompanied car'. Befriended by our ship's purser,

George was advised to jump into the Land Rover at midday when

all good Frenchmen are obsessed with lunch and drive like hell

through the barriers. Unbelievable success. But what of the

gundis? Some were dead but the others were revived over what

Rover are pleased to call a heater. The survivors returned to

England tucked snugly inside Wilma's T-shirt and entertained

us with their whistles and chirps for many years.

Wilma

George © 1984

|